History

Development of the notarial activity from the Old Regime to the Confederate Valais

a. The appearance of the burgher franchises

As early as the 12th century, it was noted that the vassalage tributes, which ensured the cohesion of the feudal regime in a well-established hierarchy, had become simple loyalty services, object of contradictory alliances and allegiances. Moreover, the feudal coercion had never completely penetrated the alpine valleys. In consequence, the Counts of Savoy could no longer really rely on the “loyalty” of their vassals. Given the alpine crossings’ strategic importance, they preferred to ensure the “loyalty” of the burgher communities established along the communication routes, by granting the franchises in exchange for taking a loyalty oath. This is how the community of Sembrancher obtained from Amédée IV of Savoy, on 20 July 1239 and for the first time in Valais, a concession of franchises with the right to hold fairs and markets, to open a staging post and to transport goods (the right to store with exemption of tolls). The burgher of Sembrancher was also granted its own jurisdiction over the communal lands exploited by community’s farmers. Sembrancher then became a free town and its burghers were freed of all subjection, under the sole and direct dependence of the Count.

These franchises granted to burghers thus made up for the growing weakness of vassal homage, which concerned individuals. These franchises constituted in fact and in law a transfer of jurisdiction from the lords to the burghers. Canon Pelluchoud, historian of Sembrancher, rightly wrote : “ These burghers did not take long to adorn themselves with the title of nobility, it was in fact a collective nobility which was not open to anyone; they came to form closed castes which were as jealous of their franchises and their customs as the lords were of their privileges”.

This was all the more marked in Sembrancher as this free town then became the siege of a castellany, the man constituency of the Savoyard administration conceived by Count Peter II of Savoy. The noble burgher of Sembrancher, jealous and concerned about its rights and privileges, had its franchises renewed and specified for the first time in 1322 by the Duke Amédée V of Savoy then, on several occasions, by the Savoyard sovereigns, until 26 March 1466 by Duke Amédée IX. At the end of the Savoyard regime (1475), the Haut-Valaisans and the Bishop of Sion also recognised them, as did the Bishop of Platéa in 1523.

b. The growing importance of the notary in the burgher communities

Within the framework of their franchises, the burgher communities organised themselves administratively. The mayors, annually appointed by the assembly of burghers, took care of the finances and the community’s properties’ administration, while the legal offices were administered with a certain permanence by the castellan and his lieutenant.

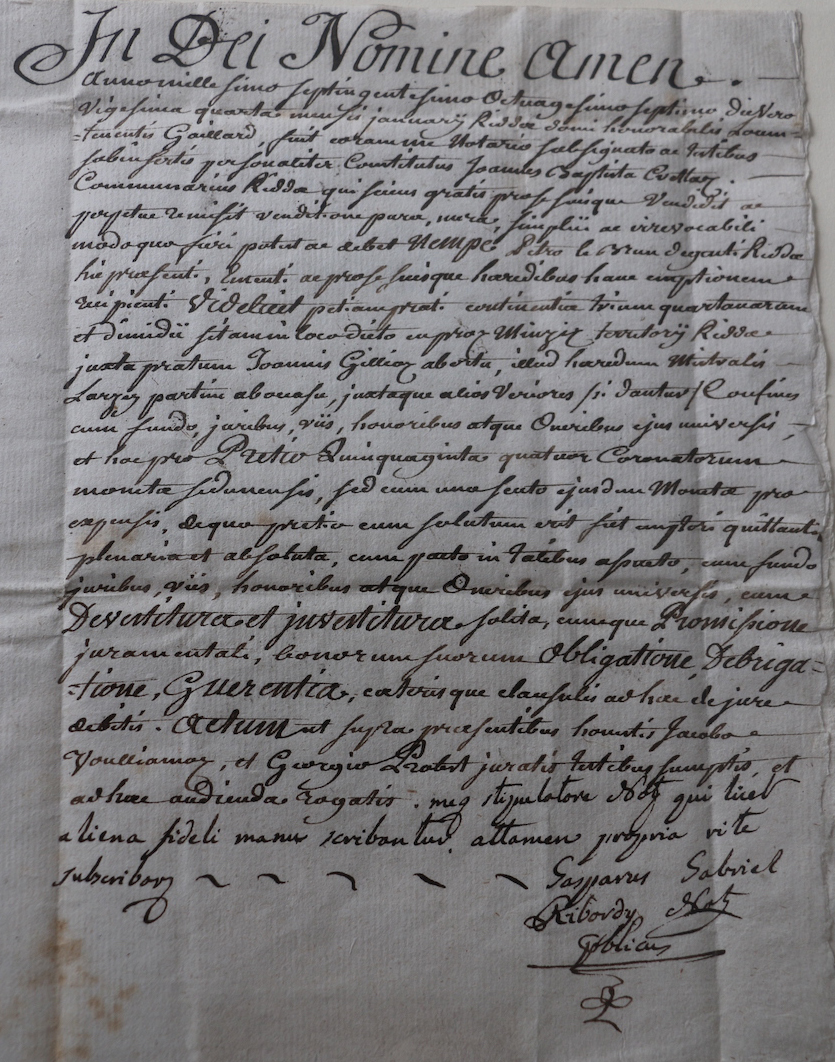

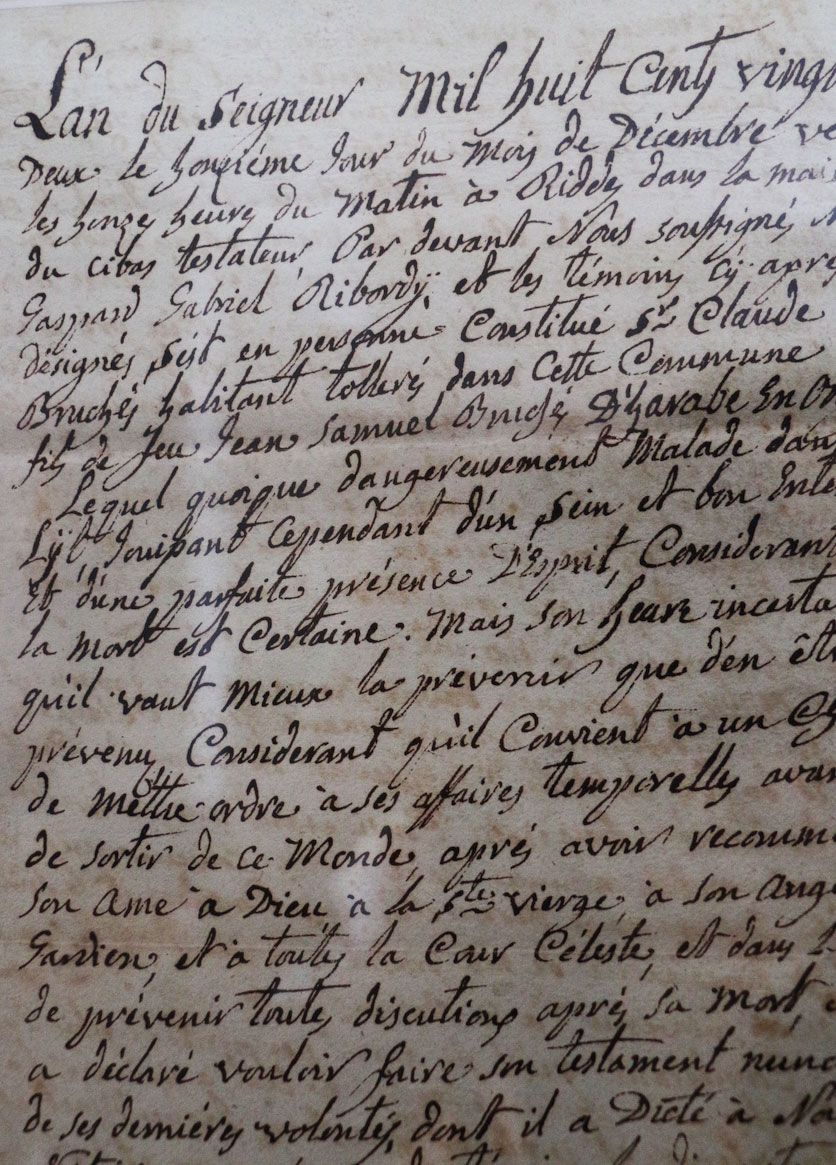

In 1571, Antoine II Ribors already held the position of lord of the castle with the Fabri and Loës families. Alongside him, the parish was the official notary of the castellany, as well as the officer of justice who had the exclusive and particularly lucrative right to stipulate certain legal deeds, such as wills, and to institute tutelages. The development of notarial activity in the castellany of Sembrancher should be examined in these circumstances.

At the end of the Savoyard regime, the situation did not change much. After the conquest of the Bas-Valais in 1475, the diet and the Bishop of Sion also had to rely on the local political and judicial administration to try to assure their jurisdiction over the conquered territory. As in the Savoyard period, the use of writing was indispensable for the exercise of this jurisdiction: notaries were therefore naturally called upon to play an increasingly important role, not only as officers of the court (castellan), but also to transmit the will of the sovereign to the local community. In addition, after the conquest of 1475, the fiefdom holders also had to use the services of notaries to establish the recognition of their fiefs with the feudal lords. They were also often called upon to defend the rights of the burghers in the exercise of their franchises against the Diet, the bishop, or other feudal lords.

Because of their distance from the main administrative centres in Savoy, and later from Sion, notaries of Entremont benefited of a relative independence, reinforced by the considerable resources they were able to draw from their activities. The establishment of their castellany such as that of Sembrancher, located on an important transalpine communication route, a centre of trade and transit with fairs, markets and storage, promised them important sources of income, including through the establishment of exchange bills or endorsed debts, which were very common payment instruments at a time when roads were not very safe, as well as through the stipulation of written contracts relating to the trade of goods acquired through brokers.

Thanks to this situation and its multiple activities, the notaries gradually acquired a certain material wealth that allowed them to emerge in collective community relations before the local burghers, of whom they are naturally called upon to defend the interests.

c. The emergence of notary families

Initially carried out by the ecclesiastical chancelleries, the practise of notary was not engraved in the intrinsic nature of the feudal system, where the lord’s power was essentially based on the possession of land and the income derived from it. Though the notaries were not subject to the same severe seigniorial fees as peasants, the feudal power nevertheless tried to control their income the intermediary of various chancelleries (which were in competition against each other, especially the capitular chancellery of Sion, that of the Abbey of Saint-Maurice d’Agaune and that of Savoy), in the same that it tried to impose tolls on merchants of taxes on goods sold at fairs and markets. This is how some deeds hat to be sealed with the seal of the curia to be authenticated. However, the rivalry between the various chancelleries and the difficulties the sovereign had to enforce the rules laid down benefited the notaries.

For example, despite the Valais statutes of 1571 that prohibited this, the heirs of a deceased notary could keep his minutes, which encouraged, as with the Ribordys, the recurrence of the notary's office within the same family. These statutes also confirmed the Savoyard principle of remunerating the notary according to a fee payable in cash, in proportion to the market value of the property covered by the contract. In an essentially agricultural economy where exchanges and the payment of royalties were most often carried out in kind, the principle of remuneration in cash provided notaries with a real economic advantage which did not fail to have a decisive influence on their social status. It is interesting to note that, in his work on "La Maison du Grand Saint-Bernard", Canon Lucien Quaglia listed among his creditors, in 1592, the names of Pierre Challand of Bourg-Saint-Pierre and Antoine II Ribors, lord of Sembrancher, who were both notaries (cf. Genealogical tree).

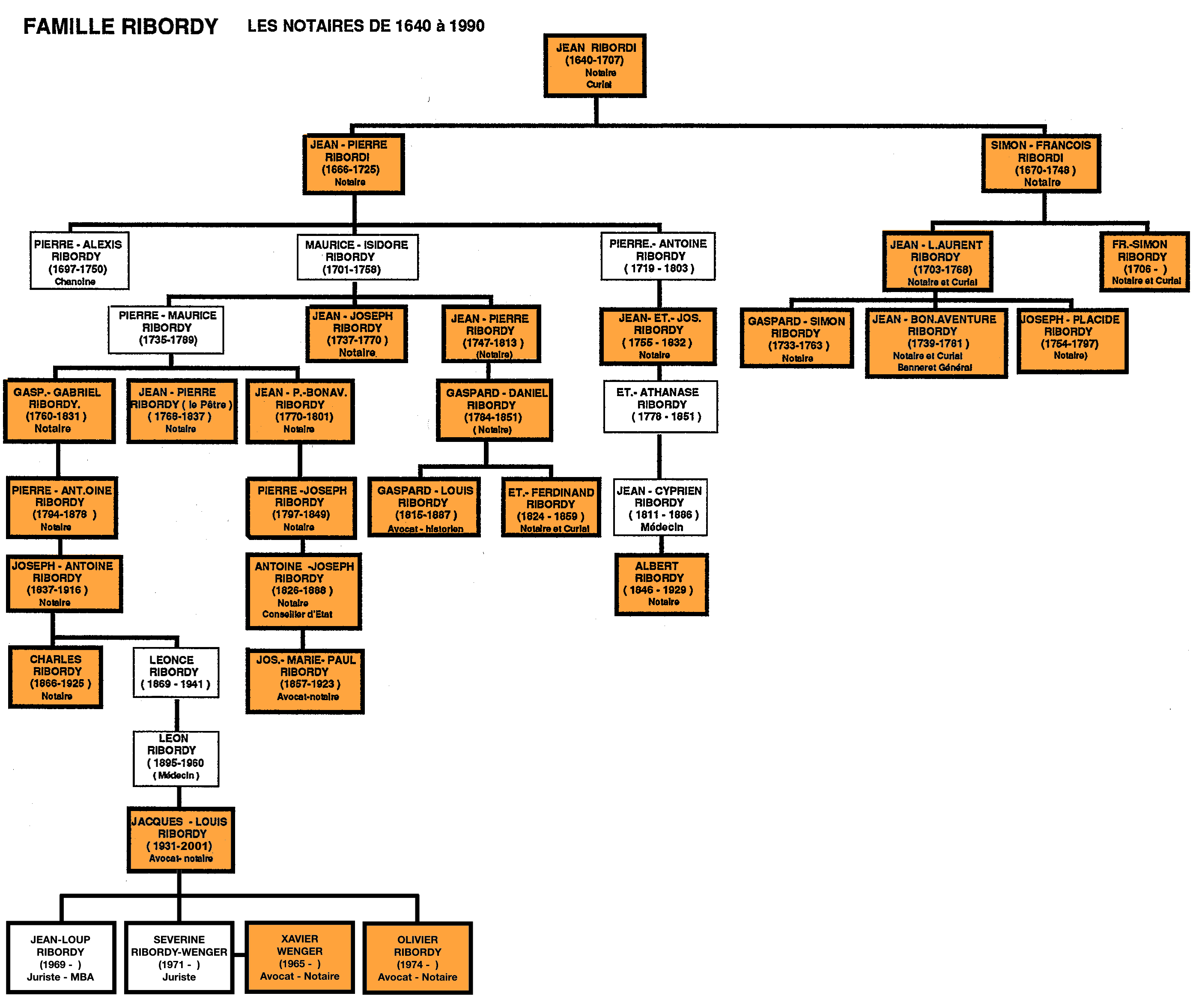

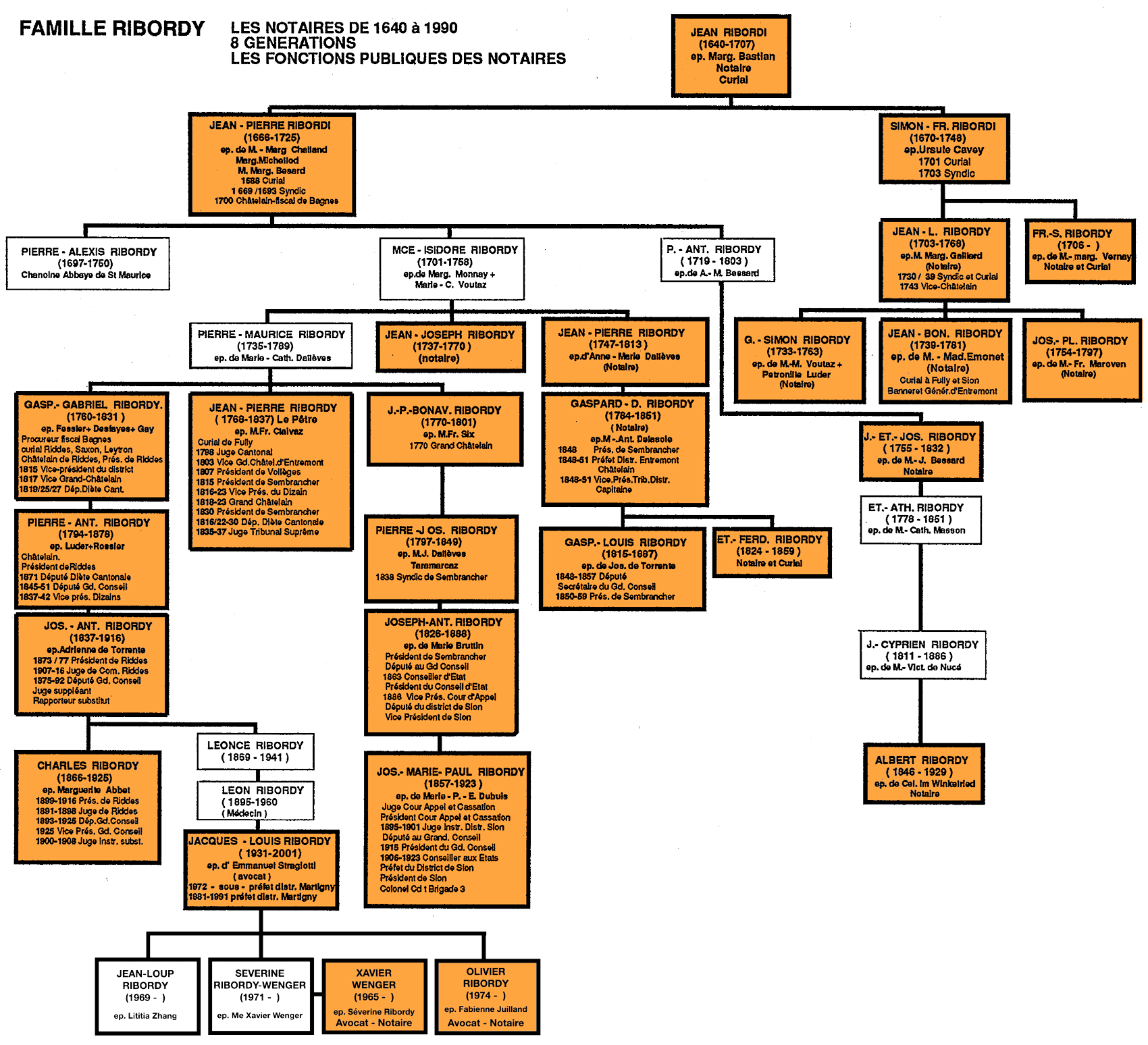

In his study, Françoy Reynauld noticed that in the municipality of Bagnes, “kinship relationships were formed among the notaries. The ties that are created can serve as an indicator of a certain affluence that distinguishes notaries from the rest of the population: in fact, the families of notaries recognise, at least among themselves, a particular status; any professional endogamy reflects a certain awareness of common interests and, as with the peasants, there is a desire to preserve one's patrimony within the family; from this point of view, the constitution of families of notaries is certainly an effective means". This was also the case in Sembrancher. Jean VII Ribordi (1640-1707) married Marguerite Bastian, his son Jean-Pierre Ribordy (1666-1725) in turn married Marie-Marguerite Challand, both of whom belonged to important notary families, who held the metralies of Liddes and Bourg-Saint-Pierre. The genealogy of the Ribordy family has multiplied the alliances with the Dallèves, Voutaz, Delasoie etc. families. They were all allied to the Fabri, de Loës, Medici, Volluz families, who also had many notaries. Without counting Antoine II and Jean III who were clerks and notaries in the 16th century, there are now 26 notaries with the same surname in the descendants of Jean VII Ribordi, born in 1640, who were established successively in Sembrancher, Bagnes, Riddes, Sion or Martigny and who almost all held political or judicial positions at all levels (cf. Genealogical tree)

From the beginning of the 17th century, it was noticed that the local communities were gradually consolidating their autonomy. They particularly strengthened their judicial administration, which had the effect of increasing the role and importance of the officers of justice (castellan and curial) and therefore the position of the notaries. The latter held positions that were not renewed every year, such as the office of syndic, but which could be held by the same person often for more than a decade. This permanence increased the influence of the officer of justice on these citizens. Gradually, the traditional social organisation of the community changed in favour of the predominance of certain families over others, over several generations. This gave rise to the typically Helvetic institution of patriarchy. The patriarchal system consisted of those families whose members had the greatest influence in the community, particularly through their control of the political and judicial functions that they shared.

The study of the transmission of communal or dezenal functions from one generation to the next, or the multiplication of different functions successively occupied by the same person, in Sembrancher as well as in Riddes or Sion, along with the alliances contracted, were an illustration of this. It is interesting to note that this transmission took place despite the break-up of 1798 or the entry of the Valais into the Confederation in 1815, or even despite the new Constitution of 1848.

As a foreign observer, François Raynauld noted that "this continuity is partly justified by the cohesion of the dominant class faced with a peasantry that does not seem to openly express its disavowal of the political practices taking place before its eyes; it is that patriarchy was partly justified by the peasant custom surrounding the inheritance of the farmer's landed estate, and the latter forgave the notarial elite for extending these principles to the inheritance of judicial functions. This is a new opportunity for the elite to define themselves the rules of operation of an activity, thus consolidating their power. In this respect, it should not be forgotten that Article 18 of the Valais Constitution of 1815 stipulated the following: "To be elected to the Diet, one must be at least 25 years of age, have held legislative, judicial or administrative office in the higher authorities or in the tenain, have exercised the office of notary public or be a graduate, a doctor in the faculties of law or medicine or, finally, have held the rank of officer in the line troops. "

Thus, the transition from the old regime to the confederated Valais was smooth and allowed the notaries to transform, through a constitutional article, the exercise of supreme power into a monopoly almost identical to that of the landowning lords of the old regime.

Thirty generations of notaries

| 1 | 1490-1550 | Ribors Pierre III |

| 2 | 1510-1573 | Ribors Antoine I |

| 3 | 1539-1600 | Ribors Jean III |

| 4 | 1540-1600 | Ribors Antoine II |

| 5 | 1640-1707 | Ribordi Jean VII curial |

| 6 | 1666-1725 | Ribordi Jean-Pierre de Jean |

| 7 | 1670-1748 | Ribordi Simon-François de Jean |

| 8 | 1703-1748 | Ribordy Jean-Laurent de Simon-François curial |

| 9 | 1706- ? | Ribordy François-Simon de Simon-François curial |

| 10 | 1737-1770 | Ribordy Jean-Joseph de Maurice-Isidore |

| 11 | 1747-1813 | Ribordy Jean-Pierre de Maurice-Isidore |

| 12 | 1755-1832 | Ribordy Jean-Etienne de Pierre-Antoine |

| 13 | 1733-1763 | Ribordy Gaspard-Simon de Jean-Laurent |

| 14 | 1739-1781 | Ribordy Jean-Bonnaventure de Jean-Laurent banneret d'Entremont |

| 15 | 1754-1797 | Ribordy Joseph-Placide de Jean-Laurent |

| 16 | 1760-1831 | Ribordy Gaspard-Gabriel de Pierre-Maurice |

| 17 | 1768-1837 | Ribordy Jean-Pierre de Pierre-Maurice |

| 18 | 1770-1801 | Ribordy Jean-Pierre-Bonnaventure de Pierre-Maurice |

| 19 | 1784-1851 | Ribordy Gaspard-Daniel de Jean-Pierre |

| 20 | 1794-1878 | Ribordy Pierre-Antoine de Gaspard-Gabriel |

| 21 | 1797-1849 | Ribordy Pierre-Joseph de Jean-Pierre-Bonnaventure |

| 22 | 1815-1887 | Ribordy Gaspard-Louis de Gaspard-Daniel |

| 23 | 1824-1859 | Ribordy Etienne-Ferdinand de Gaspard-Daniel |

| 24 | 1837-1916 | Ribordy Joseph-Antoine de Pierre-Antoine |

| 25 | 1826-1888 | Ribordy Joseph-Antoine de Pierre-Joseph |

| 26 | 1846-1929 | Ribordy Albert de Jean-Cyprien |

| 27 | 1866-1925 | Ribordy Charles de Joseph-Antoine |

| 28 | 1857-1923 | Ribordy Joseph-Marie-Paul de Joseph-Antoine |

| 29 | 1931-2001 | Ribordy Jacques-Louis de Léon |

| 30 | 1974- | Ribordy Olivier de Jacques-Louis |